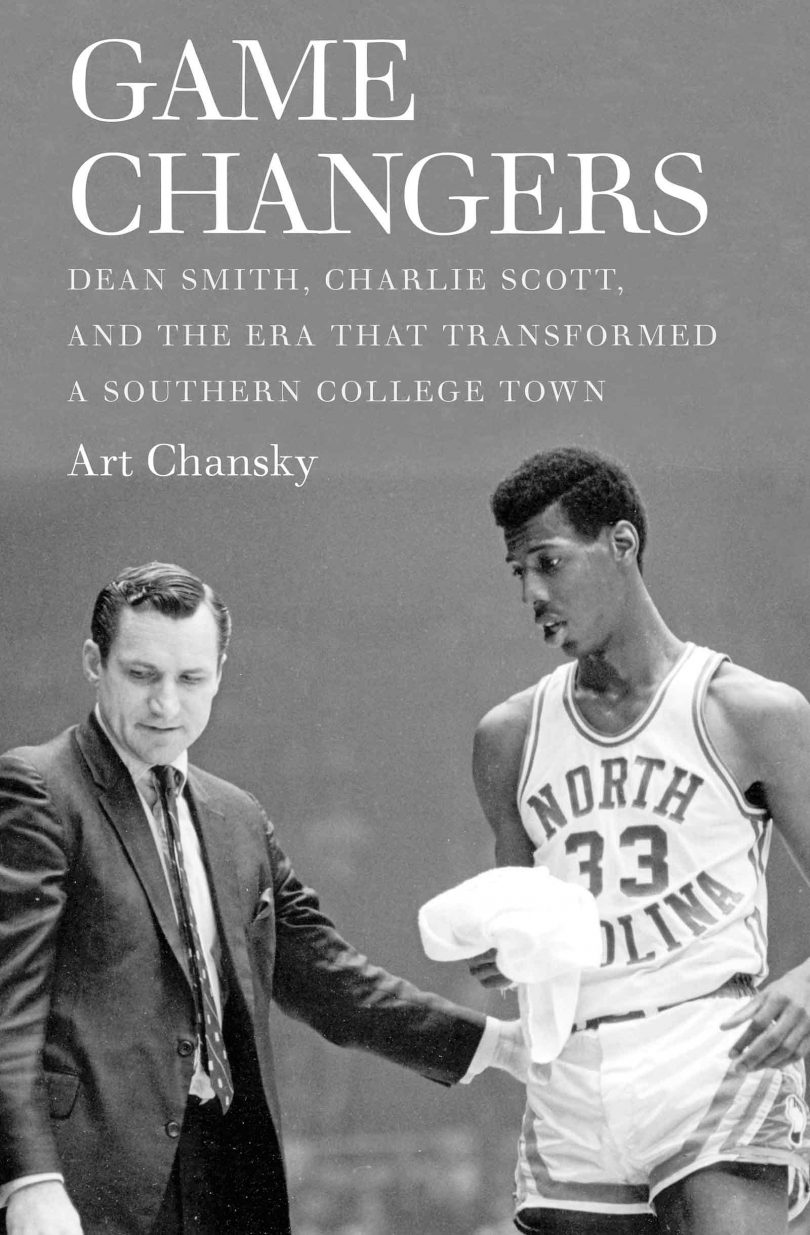

“Game Changers,” Dean Smith and Charlie Scott, by Art Chansky, UNC Press, 224 pp, $26.00

Joel Bulkley

Sportswriter Art Chansky has written four books on North Carolina basketball and Dean Smith. His latest isn’t a hard-care hoops book. It’s a history book, mixing an examination of the civil rights struggle in Chapel Hill in the 1960s with behind-the-scenes stories on the recruiting and college career of basketball star Charlie Scott, UNC’s first Afro-American scholarship player.

It’s informative and occasionally critical of the parties involved in the civil rights demonstrations and maybe less than complete on the civil rights part, but adds a different and more candid perspective than John Ehle’s “The Free Men.”

Chansky says Chapel Hill was not as progressive as its reputation and was more like “an old Southern town.”

As a reporter covering the demonstrations for the Daily Tar Heel in 1963-64, I agree but dispute the chronology of some protest events in the book but the overall picture provided was pretty accurate. Chansky’s book seems based primarily on interviews with business and church leaders. The sit-ins began in 1960 but were stepped up in 1963-64, with hundreds of arrests.

Despite its lofty reputation, the town failed to pass a local public accommodations law (approved in Durham after only two days of massive protests), dragged its feet on school integration and moved at a snail’s pace toward racial equality. For example, it took the 1964 Civil Rights Act to integrate the dozen or so holdout segregated bars and restaurants. They all complied after the law was signed by President Johnson when a black minister and I checked that afternoon and were served coffee and apple pie.

UNC leaders were thought to be neutral about civil rights protests (according to Chansky), but they really wanted them to go away. The DTH editor and I were called to the Dean of Student Affairs Office to talk about why the paper had daily stories on civil rights protests in Raleigh and Chapel Hill. Gary Blanchard, the co-editor, explained that when UNC students were arrested, the UNC student paper intended to do stories. That was the end of that.

Scott arrived at UNC in 1966 from Laurinburg Institute as one only a handful of black UNC students when Dean Smith was struggling to build his basketball program. Scott starred on the freshman team (where he reportedly was booed at his first home game but never again at UNC; not mentioned in the book).

He joined the varsity the next year and his career skyrocketed. Scott graduated in 1970, signed with the Virginia Squires of the ABA and played ten years in the pros, winning a championship with the Boston Celtics.

Scott was a key player on the 1968 and ’69 ACC championship and Final Four teams, two-time All-America and three-time All-ACC selection, averaged 22.1 ppg and 7.1 rebounds. Scott was an Academic All America and won a gold medal at ’68 Olympics in Mexico City.

The Chansky book goes into detail on key games and explains Scott’s relationship with his coach, teammates, some opponents, as well as Smith’s family background (his father was a high school coaching pioneer in Kansas) which led Dean’s decision to recruit Scott and other black players).

Meanwhile, Smith, under fire for not being as flashy or successful as previous coach Frank McGuire, was quietly building a powerhouse with strong recruiting and innovative coaching. UNC went from 16-11 in 1965-66 to 26-6, 28-4, 27-5, 26-6 over the next four years.